Field investigation for the Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Kasese. Photo credit: Kasese Local Government

In the early months of 2024, Evaristo Ayebazibwe, a monitoring and evaluation officer at Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation – Uganda, introduced the 7-1-7 target to district leaders, health teams and cultural leaders in the Kasese District. They were experiencing an outbreak of measles, and Ayebazibwe thought it could help the response.

“It was a real scenario on the ground” he said.

The district had never used the performance improvement approach, which recommends detecting an outbreak within seven days, notifying public health authorities in one day, and initiating an effective response in seven days. But deploying 7-1-7 amidst the measles outbreak gave it an added sense of urgency.

Battling bottlenecks

On January 29, a village health technician encountered three children in the community of Nyamambwa experiencing the telltale rash, high fever, and other characteristic symptoms of measles. The first child affected had symptoms start on January 21. The technician encouraged their parents to take the children to a local healthcare facility for a definitive diagnosis. The person tasked with disease surveillance collected samples from the children at the facility, sent them for testing at the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Kampala and notified the Kasese district surveillance focal person the same day. The next day, a rapid response team deployed to the area. They collected additional samples from children with similar symptoms and submitted them for testing on February 2.

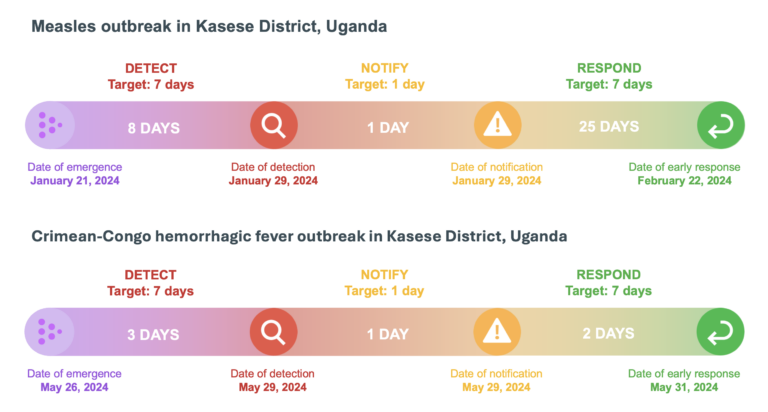

Ayebazibwe’s introduction of the 7-1-7 target during the outbreak helped the district’s political and health leaders recognize that the district’s response times were falling short of the 7-1-7 target. The health workers detected the first case in eight days and notified public health authorities in one day, but it took 25 days to initiate the response. The analysis also helped them understand enablers and bottlenecks that affected their response times. They discussed how they lacked designated response funds or a work plan to quickly release necessary resources in the event of an outbreak.

“They did not have the funds or resources ready to support the district response teams moving in and investigating,” Ayebazibwe explained. For example, they lacked the necessary fuel and vehicles to get them to the affected communities quickly and ready access to vaccines to help curb the spread of the highly contagious virus. Ultimately, a total of 24 cases were confirmed before the outbreak ended.

Uganda’s Kasese district demonstrated rapid improvement after the 7-1-7 target was first used during a measles outbreak in early 2024.

Empowering leadership

Information about the enablers and bottlenecks empowered decision makers to take the steps necessary to improve their response times. They were able to put a new protocol in place to quickly deploy public health care funds in the event of an outbreak. The district also set aside immediately accessible funds for outbreak response and worked with outside partners to mobilize additional resources.

“Once the political leaders and decision-makers are oriented to the 7-1-7 metrics, mobilizing resources and achieving the timelines becomes easy,” Aybazibwe explained.

Those preparations and decisive leadership decisions helped dramatically improve the Kasese District’s response times when an outbreak of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever was detected on May 29, 2024, at a health facility in the Busongora-North subdistrict. A 29-year-old man from Kayanja 1 village had been experiencing a high-grade fever, muscle aches, dizziness, headache, nausea, and vomiting for three days and had recently removed a tick from his body.

Health workers recognized the man’s condition as a suspect case of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever, which can be spread by tick bites. They reported the case to the district’s brand-new surveillance officer, Arafat Bwambale.

“It was my baptism by fire,” Bwambale said. “People started saying we might be dealing the Marburg virus or Ebola.” The highly infectious and deadly viruses share some symptoms with Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever and have caused large outbreaks in some African countries in recent years, including in Rwanda which is currently battling Marburg.

Bwambale agreed with the facility staff that Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever was the likely cause of the symptoms and instructed the health facility surveillance focal person to isolate the man, collect a sample, and send it for testing at the Uganda Virus Research Institute. The Ministry of Health and the National Public Health Emergency Operation Center notified the district health officer and the district surveillance focal person when the sample tested positive the next day. Using their new protocols and what they learned during the measles outbreak, the district deployed the District Rapid Response Team within 24 hours of notification.

District leaders’ decisive actions allowed the district to detect the virus in three days, notify relevant authorities in one day, and launch an effective response in two days, meeting the 7-1-7 target. The index case was the only person who tested positive, though three other suspected cases were isolated and tested. The infected man survived and recovered due to his rapid identification and care.

We learned our lessons during the measles outbreak. We must work together once the notification comes in and immediately swing into action to control an outbreak.

Arafat Bwambale, Kasese District's surveillance officer

Replicating success

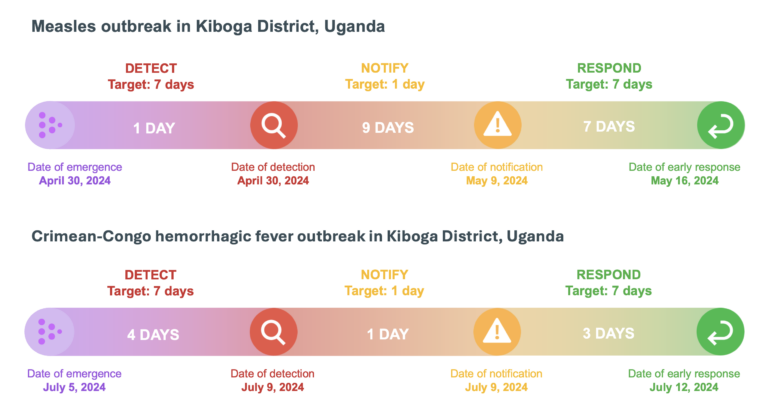

Like Kasese, Kiboga district’s use of 7-1-7 led to rapid improvement and the timely detection, notification and early response to a Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever outbreak.

Uganda’s Kiboga district experienced similar success in speeding its outbreak response times using the 7-1-7 target on a pair of outbreaks.

With technical support from Mercy Wanyana, an event surveillance analyst at the Mubende Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC), the district’s public health teams applied 7-1-7 during a measles outbreak. The first cases were detected within a day when a group of children with suspect symptoms sought care at the Lwamata Health Center. Notification, however, took nine days because some frontline health workers, especially at private facilities, didn’t know how to report and those that did relied on submitting paper forms. However, once notification was made, the district completed initiation of early response actions and deployed measles vaccines to the affected area within seven days, despite initial challenges in accessing resources including response funds, vehicles, fuel, and vaccines.

In the wake of the outbreak, district leaders immediately went to work correcting the bottlenecks discovered during the 7-1-7 analysis. Health workers were taught how to report suspected measles cases using electronic forms, and improved data-sharing protocols between health facilities and district staff were initiated.

“We needed to reorient [frontline workers] on the importance of early detection, how to do it, and we needed to share standard case definitions of common conditions,” said Noah Luwalogga, the district surveillance officer. “We needed to empower local communities and brief them.”

That work paid off when a case of Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever was detected in July in a 27-year-old man from a neighboring district who sought care in Kiboga. Despite an initial misdiagnosis, detection took just four days, notification one day, and completion of the early response actions in three days. In fact, the district health team met the same day they were notified and began mobilizing the response, which included case management, surveillance, and communication with the public via radio and other means.

Wanyana said that using 7-1-7 created a sense of urgency to meet the target and influenced decision-making for immediate performance improvement.

7-1-7 helped improve coordination. It helped reduce siloed approaches to case management, surveillance, and communication.

Mercy Wanyana, event surveillance analyst at the Mubende Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Center

Uganda was the first country in October 2021 to pilot the 7-1-7 target for continuous real-time performance improvement and use results from 7-1-7 analyses to prioritize activities for financing. The Ministry of Health, with support from partners like the Infectious Diseases Institute, Resolve to Save Lives, Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation – Uganda, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, created a supportive environment to expand 7-1-7 use at the subnational level. All 13 regional PHEOCs received training from the ministry between the end of 2022 and mid-2023.

“Collaborations with government, development and other implementing partners like Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation – Uganda has supported rapid scale up of the framework to the 13 regions trained on 7-1-7,” said Lydia Nakiire, country lead for 7-1-7 in Uganda.

“Uganda has made progress in the implementation of the 7-1-7 target,” said Dr. Issa Makumbi, director of Uganda’s Public Health Emergency Operations Center. “Under the Ministry of Health’s regionalization approach, the national and regional public health emergency operation centers have made it possible for districts to use 7-1-7 and rapidly improve their response to health threats. Solutions to our challenges reside in both the political and technical arenas.”