New analysis of 7-1-7 data across 12 countries shows a clear pattern: health authorities detect and report vaccine-preventable disease outbreaks fast—but they take longer to respond. Only 39% meet 7-1-7’s seven-day response target. We have the vaccines, tools and response structures, but delays in systems are costing lives.

Vaccines have saved 154 million lives over the past 50 years. They remain our most powerful weapon against infectious disease outbreaks. Yet with vaccine hesitancy on the rise, active misinformation from previously trusted sources, and increased global mobility, outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease (VPD)–– infections caused by viruses or bacteria that can be stopped through vaccination––are becoming more common.

Surprisingly, even countries with a strong track record of containing novel pathogens or rare diseases struggle with VPD outbreaks, even though we have proven interventions ready to deploy. 7-1-7 data from 12 countries reveal that VPDs consistently face longer response delays than any other outbreak category. And these delays are costing lives.

Why timeliness matters

The early days of an outbreak offer a narrow window of opportunity to bring the outbreak under control quickly. By deploying vaccines quickly, countries can stop exponential spread in its tracks. New modeling from the Burnet Institute suggests that speed matters––if outbreak vaccination begins at 15 days instead of current averages, it can result in:

- Cholera: ~80% fewer cases

- Meningitis: ~35% fewer cases

- Measles (low coverage): up to 55% fewer cases

- Yellow fever (high risk): up to 35% fewer cases

The performance gap: VPD outbreaks are missing the 7-1-7 target

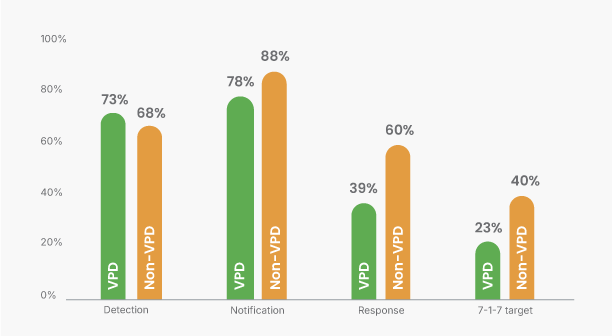

7-1-7 timeliness performance, VPD vs. non-VPD—109 VPDs outbreaks (from WHO’s Essential Programme on Immunization disease list) from 12 countries were analyzed against 484 non-VPD outbreaks from 20 countries.

In our timeliness analysis of 109 VPD outbreaks, a clear pattern emerged. While detection and notification were reasonably strong (73% and 78% of outbreaks), the system fails when it comes to response. Only 39% of VPD outbreaks completed early response actions within seven days of notification versus 60% of non-VPD outbreaks. This means that VPD outbreak are 35% less likely to meet the seven day response target compared to non-VPD outbreaks.

And because the 7-1-7 target requires meeting all three components, less than one in four outbreaks achieved the full target (23%)—compared to two in five non-VPD outbreaks (40%).

Not all VPDs are created equal

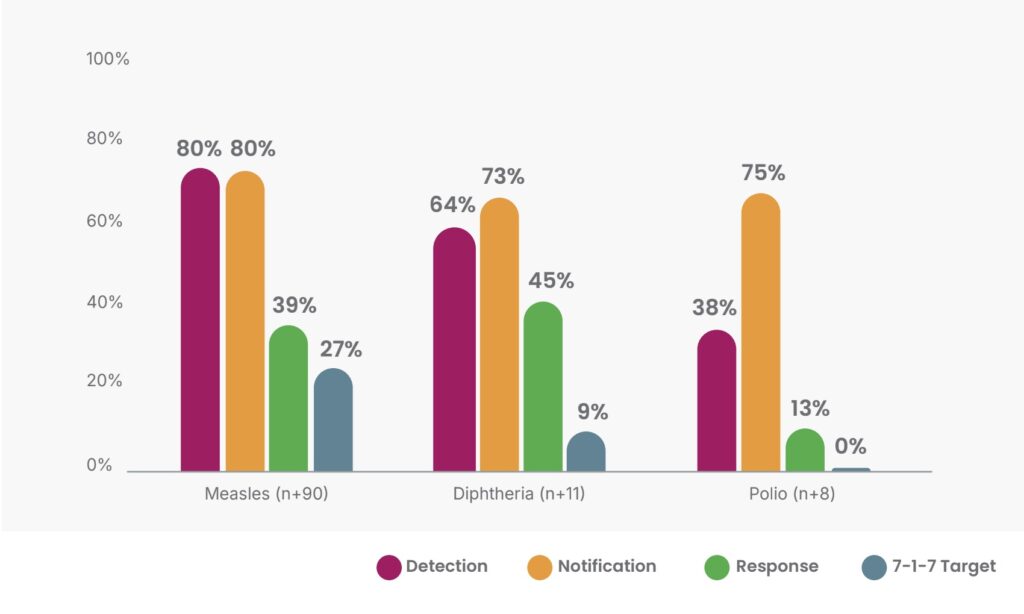

7-1-7 VPD timeliness performance by disease—measles, diphtheria and polio. Fewer than half of measles outbreaks reached the 7-day response target. Only 9% of diphtheria outbreaks met the full target. Zero percent of polio outbreaks in our dataset met the full 7-1-7 target—likely linked to limited in-country capacity.

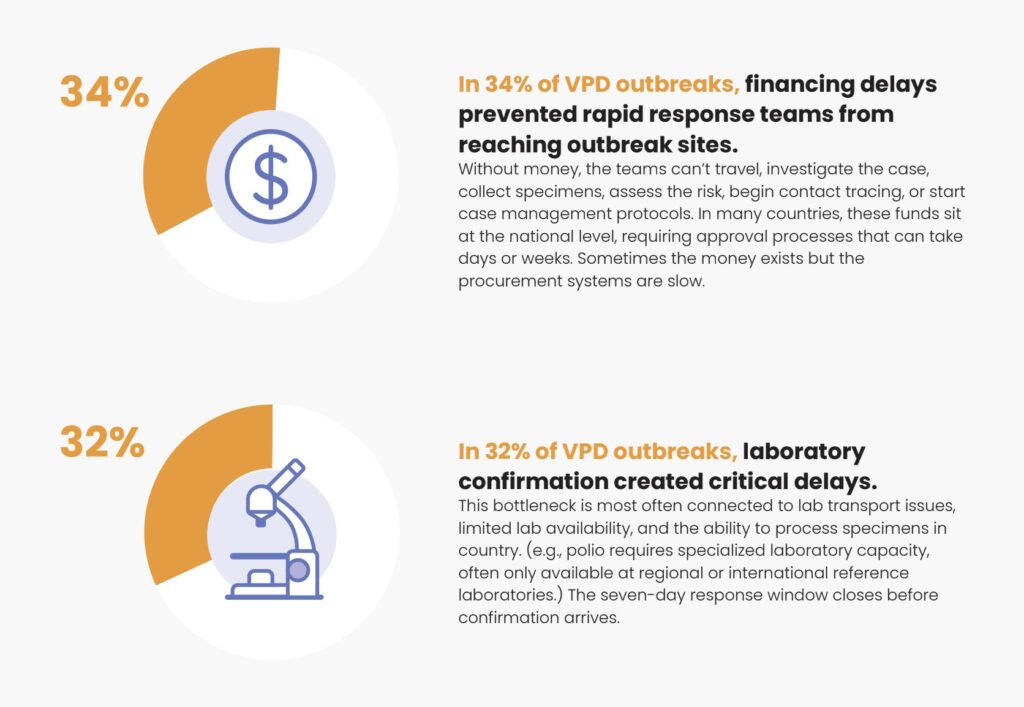

Why response is delayed: Understanding the bottlenecks

Bottlenecks are concentrated in the early response phase, specifically around response initiation and laboratory confirmation. For polio, a disease targeted for global elimination, delays can occur from sample collection to final sequencing to confirm the specific strain (wild-type or vaccine-derived) due to delays in sample collection, transport, and multiple laboratory processing steps following strict criteria.

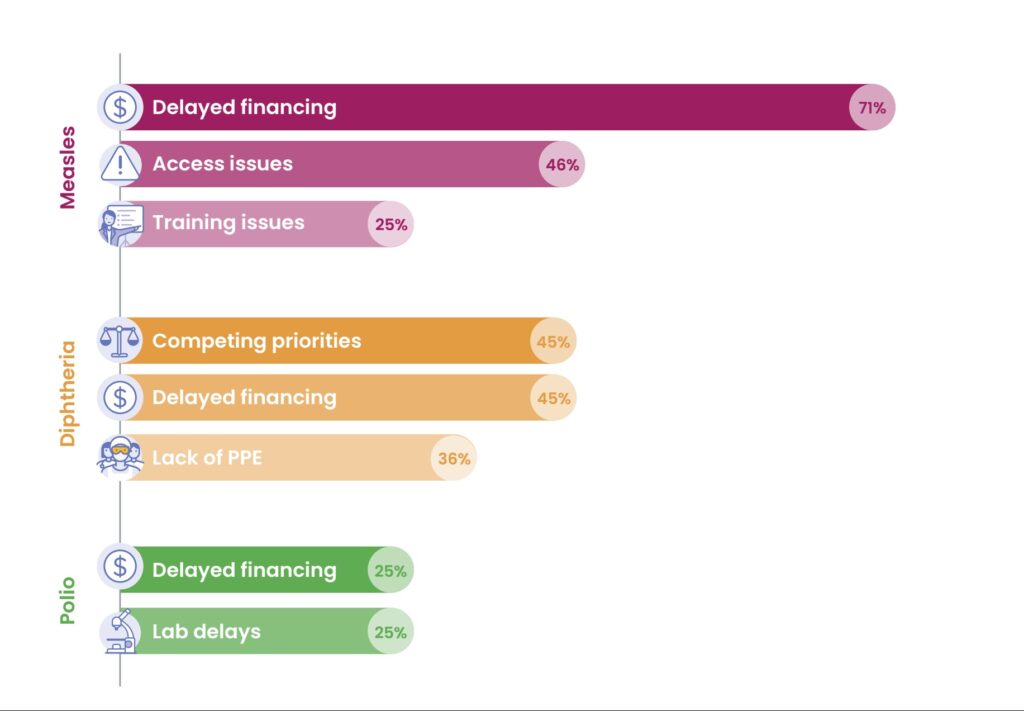

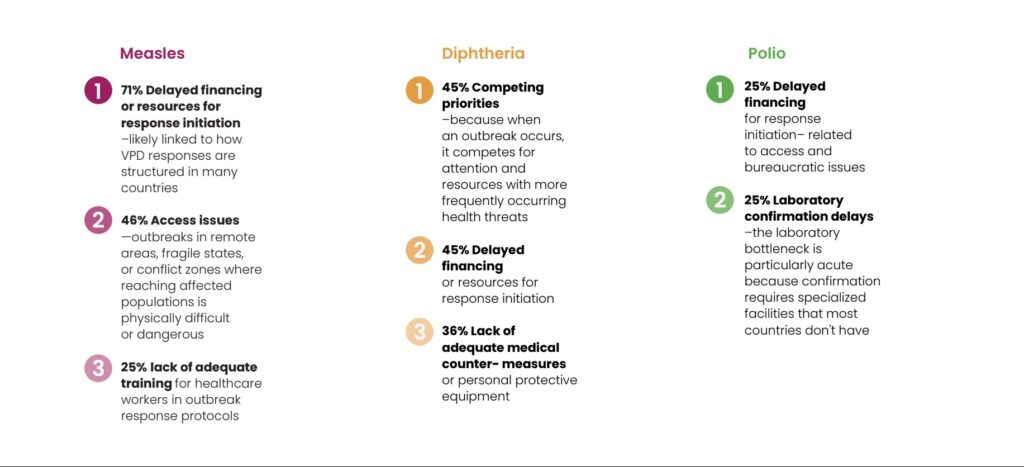

Top 3 bottlenecks by VPD

How we can do better: Solutions that work

1. Don't wait for outbreaks to vaccinate

The best solution to a VPD outbreak is preventing it from happening in the first place. Countries must continue strengthening routine immunization programs and responding to declining vaccination rates proactively rather than reactively. When routine coverage falls below protective thresholds, conduct integrated vaccination campaigns before outbreaks occur.

2. Integrate incident management approaches for VPD outbreaks

In many countries, VPD response is managed by routine immunization programs. In this context, they frequently experience coordination gaps, funding delays and siloed decision-making. The solution is to better align VPD outbreak management to public health emergency response workflows or incident management systems. This is particularly critical at subnational levels, where most VPD outbreaks are detected and where early response actions must occur.

What success looks like: Nimba County, Liberia

When a measles outbreak emerged in the Saclepea Mah District in Nimba County, Liberia, in 2024, integrated coordination mechanisms helped the surveillance and Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) teams work together to swiftly contain it. Authorities achieved the 7‑1‑7 target with 113 cases recorded and no death. Thanks to the immunization campaign conducted as part of the response actions, the local measles vaccine coverage increased from 74% to 97% of the population. Since then, the district recorded only one case of measles from January to October 2025.

3. Build laboratory capacity and clear specimen pathways

Countries should plan for and maintain testing capacity for VPD outbreaks that is timely and reliable. Countries can establish laboratory networks and sample transportation systems that enable prompt testing and return of results to inform public health actions. For polio, where global elimination protocols must be implemented, countries could use additional metrics to identify opportunities for improvement aligned to those protocols––e.g., 7 days for detection, ensuring two samples arrive at the testing laboratory within 7 days of notification, and ensuring laboratory confirmation of species occurs within 7 days of sample receipt––results of which would trigger immunization around the confirmed case within 14 days. Ultimately, such improvement efforts would result in a higher proportion of outbreaks meeting the 7-1-7 target.

Learn more in our post dedicated to addressing the lab-related bottlenecks.

4. Make emergency response funding immediately accessible at subnational levels

The response initiation bottleneck needs a straightforward fix: money that can be accessed without delay at the level where response happens.

This can take several forms: pre-positioned funds at district or regional levels, rapid authorization mechanisms that allow subnational officials to access emergency budgets without multi-day approval processes, or simplified procurement procedures for emergency response activities. Some countries have created revolving funds specifically for outbreak investigation and response. Others have emergency lines in their budgets that can be drawn down immediately when outbreaks are declared.

Financing systems should match the speed requirement of outbreak response. To learn more, read our post dedicated to addressing this bottleneck.

A path forward

Countries using 7-1-7 for performance improvement are already reviewing outbreak data regularly. But there’s value in looking specifically at patterns across VPD outbreaks. Are the same bottlenecks appearing repeatedly? Are certain diseases consistently underperforming? Are particular regions struggling more than others? Compiled in a 7‑1‑7 synthesis report, these patterns can directly inform national planning priorities and budget allocations. Better measurement leads to better decisions––and ultimately better outcomes.

VPD outbreaks should be the easiest to control with safe, effective vaccines and decades of experience managing these diseases. By addressing the response gap, we can save lives during outbreaks, reduce case numbers and outbreak duration, make better use of existing vaccines and resources, and build stronger, faster systems that work not just for VPDs but for all outbreak types.

Join the 7-1-7 Global Community of Practice

This is where countries share real experiences, and collective problem-solving accelerates progress on outbreak response performance.