Geoffrey Mureithi crossing a flooded area in Marsabit County (left) and presenting a poster on the use of the 7-1-7 target in the Rift Valley Fever outbreak in Marsabit County at the June 2024 Global Health Security Conference (right). Mureithi won best poster of the conference. Photo credit: FHI 360

When a Rift Valley Fever outbreak occurred in Kenya’s Marsabit County in January 2024, Dr. Jedidah Kiprop, a medical epidemiologist and emergency operation center liaison officer at the African Field Epidemiology Network, and her colleagues were ready to apply the 7-1-7 target thanks to online training tools supplied by the 7-1-7 Alliance and the technical support provided by U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 7-1-7 target aims to detect an outbreak within 7 days, notify public health authorities and initiate an investigation and response in 1 day, and initiate an effective response within 7 days. The target helped Dr. Kiprop and her colleagues to assess and adjust their Rift Valley Fever response in real time. Geoffrey Mureithi, a health informatics specialist at FHI 360, and Dr. Kiprop presented a poster describing their successful deployment of 7-1-7 at the June 2024 Global Health Security Conference. Their award-winning presentation demonstrated how the 7-1-7 target empower public health workers.

“7-1-7 is one of the simplest tools I’ve come across,” said Mureithi, who helps provide data visualization and analysis support to public health workers in Kenya. “It’s self-directed and easy to use. It is helping us learn from our mistakes and our successes.”

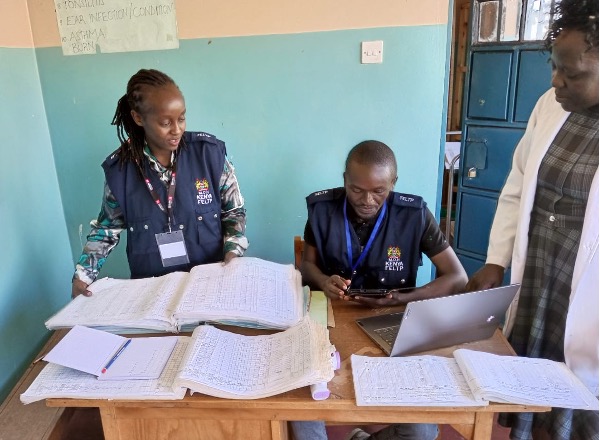

Dr. Jedidah Kiprop and colleagues work to verify data a first step in confirming an outbreak in progress. Photo credit: AFENET – KFELTP

Enablers and bottlenecks

Using the 7-1-7 target, Mureithi, Dr. Kiprop, and their colleagues found several factors that enabled Kenya’s rapid response to the 2024 Rift Valley Fever outbreak in Marsabit. Kenya’s public health authorities anticipated that forecast El Niño weather conditions in fall 2023 would increase the risk of a Rift Valley Fever outbreak. Before El Niño even started, they began rapid response training and notified pastoral communities about the risk and disease symptoms.

Most human Rift Valley Fever infections occur in individuals who handle blood or tissue from infected animals. In preparation for a potential outbreak, public health authorities used maps of area slaughterhouses to identify communities at high risk. The county’s One Health Unit, which emphasizes cooperation between human and animal health personnel, supported day-to-day response activities and facilitated human and animal health reporting.

The preparation work paid off and allowed the county to detect the first Rift Valley Fever case in 5 days—within the 7-1-7 target of 7 days. To help speed future outbreak responses, the 7-1-7 performance improvement approach recommends analyzing enablers and bottlenecks even when the target is achieved. Through this analysis, Dr. Kiprop and her colleagues identified both strengths and weaknesses they could further build on.

One of the roadblocks identified was the pastoral communities’ difficult access to health facilities and their preference for self-medication. The index case—the first person to develop symptoms—presented to the Marsabit County Referral Hospital five days after the onset of symptoms. She had worked with camels before her illness herbal medicine to treat her symptoms.

Collaboration between human and animal health authorities facilitated the rapid suspicion of Rift Valley Fever. Healthcare workers at Marasabit County Referral Hospital were already on high alert because the Kenya Animal Bio-surveillance had notified human health counterparts of an existing outbreak in camels in the area. The hospital notified the county surveillance officer of the suspected case within the target of one day.

However, it took 10 days for the national testing laboratory to notify the National Public Health Emergency Operations Center of the first confirmed human case. Dr. Kiprop explained that Marsabit County is 800 to 900 kilometers from Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, where public health workers sent batches of samples for testing. Despite the delay in laboratory confirmation, all other early response actions were met by national and county public health authorities within the target of 7 days.

Overcoming obstacles

Using the 7-1-7 target amidst the outbreak allowed public health authorities to identify bottlenecks to the response and quickly rectify them. For example, Dr. Kiprop noted that a county laboratory could test for Rift Valley Fever but lacked adequate supplies of necessary reagents. They also found that the county was lacking in emergency funds needed to roll out vaccines and other response measures.

“Without 7-1-7, which provided a very objective way to measure our response, the country wouldn’t know where the gaps were and what the low-hanging fruit was,” Dr. Kiprop said. “Once we presented these findings, the county committed to supplying the reagents. Testing samples locally will cut the turnaround time in half.”

With technical guidance from the U.S CDC, Kenya’s public health authorities have since applied the 7-1-7 target to a malaria outbreak and an anthrax outbreak. During the anthrax outbreak in the county of Muranga, the tool helped public health workers identify a pattern to the recurrent anthrax outbreaks and pinpoint carcass disposal practices as a contributing factor. “We can anticipate the next anthrax outbreak because it is seasonal, and we can put measures in place in advance to detect the first case,” she said. “The most recent outbreak was contained in less than a month—the shortest time frame yet.”

Kenya is currently conducting a retrospective review of past outbreaks in several counties using the 7-1-7 assessment and data consolidation tools. Its National Public Health Institute is also in the process of formalizing its partnership with the 7-1-7 Alliance.

The application of 7-1-7 in Kenya is giving our public health workers more confidence in approaching response to public health emergencies. Furthermore, it offers an opportunity to effectively direct resources. We are looking forward to applying this tool as necessary and across the entire country.

Dr. Victoria Kanana, health security lead at Kenya's National Public Health Institute